In 2008, during a discovery expedition organized by the Environment Ministry to search for whale fossils in the Fayoum desert, a team of scientists found a skull, jaw, two vertebrae, and several other whale bones among dozens of other fossils that the ministry collects for scientific research. For years, the head of the team, Mohamed Sameh, a paleontologist and the director of the ministry’s natural protectorates division, was confident this particular set of fossils could lead to a significant discovery.

Fossils unearthed in Egypt are commonly handed to foreign scientists for analysis, but Sameh had a different idea. He reached out to Hesham Sallam, the founder of the Mansoura University Paleontology Center, who in 2017 assigned one of his masters students, Abdallah Gohar, the task of researching the fossils under the supervision of Sallam, Sameh and three other scientists.

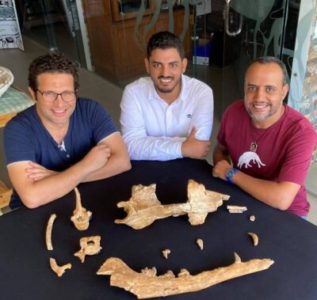

Paleontologists Hesham Sallam, Mohamed Sameh, and Abdallah Gohar. Photo courtesy of Abdallah Gohar.

After four years of work, the research team discovered that the fossils belonged to a previously unknown amphibious four-legged whale species in Egypt that lived 43 million years ago that helps trace the transition of whales from land to sea. They named the new whale “Phiomicetus anubis” and the Environment Ministry and the Higher Education Ministry announced the discovery last month in a statement that described the finding as a leap for Arab paleontologists, marking the first time that an Arab research team had led the effort to document and register a new whale species.

Let’s read Mada Masr interview with Hesham Sallam to learn more about the significance of the discovery as well as the wider context surrounding paleontology in Egypt.

***

Mada Masr: You never found the limbs of the whale, so how did you figure out that it is an amphibian?

Hesham Sallam: In biology, if we have a skull of a crocodile and I say that it belongs to an amphibious crocodile that has limbs, no one will object to that, because everyone who has seen a crocodile knows that it has legs. But this case seems strange to people because many do not know that vertebrate paleontologists had previously discovered a family of whales, referred to as “primitive or protocetid,” which have limbs and can be found in all parts of the world. For that reason, when we found the skull of a primitive whale, it was not strange for us that it belonged to a whale that had legs.

MM: What is the difference between a primitive whale and the whales that we are all familiar with?

HS: People know that whales are mammals. They procreate in a way similar to humans, where the fetus grows inside the mother’s womb and is born with an umbilical cord attached to the mother. After the birth, the newborn is breastfed just like any other terrestrial mammal, such as a cat or elephant. But how can a mammal live under water? And if it lived on land, then where are its legs? When scientists tried to answer both of these questions by excavating the ancestors of whales and examining their evolutionary history, they found that the whales that currently exist in seas and oceans are simply creatures that evolved from a more primitive species that lived on land and then moved to the water after millions of years.

MM: What is the shape of the Egyptian whale that you discovered?

HS: What we documented in our latest research is an intermediate link in the chain of evolution of different whales – a whale that still had four limbs capable of moving on land. Those limbs evolved into fins that allowed whales to swim efficiently in a way similar to contemporary crocodiles.

This type of whale is an intermediate link between the second and third family of ancestral whales. The first family of whales started with a creature similar to the fox in shape and size. It was a completely terrestrial creature, then it slowly and gradually started associating with water, either to find sources of food or to cool its body temperature. As time went by, its body evolved to adapt to living underwater. This is when the second and third families of whales appeared and they in turn developed elongated tails and experienced a transformation in their pelvic floors, skull structure and limbs. The limbs, or legs, began evolving to fins to facilitate swimming.

Here in Egypt, specifically in Fayoum, we’re very lucky to have fossils that can document this period when the terrestrial whale evolved into a marine animal.

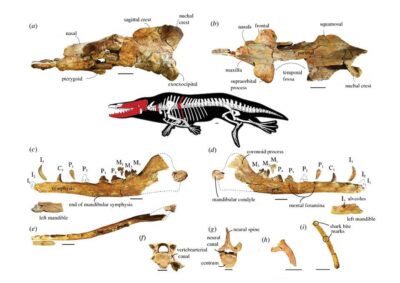

The bones of the discovered whale. Source: Cabinet Facebook page.

MM: Apart from the scientific value of the discovery, what is the significance of this to Egyptian scientists?

HS: We now have a seat next to the giants on the table of science. We’re just like them. We documented a new species of whales that no one else had discovered before and we added a new creature to the animal kingdom under Egypt’s name, one that closes a gap and answers many questions related to the evolution of whales. The research also propels us to find answers to new questions.

By comparing the size and shape of the whale’s skull and vertebrae to those of primitive whales previously discovered in other countries, we were able to accurately determine the anatomical characteristics of this Egyptian whale. It is three meters long and weighs 600 kilograms. Its bite is fatal and it has an extremely strong sense of smell. The team that led this discovery is Egyptian in heart and soul. Everyone who researched and documented is Egyptian. In the past, these types of studies were only conducted by foreigners.

MM: Why did you choose the name “Phiomicetus anubis”?

HS: “Phiomi” is meant for the place that the fossils were discovered, Fayoum. “Cetus” is the Latin word for whale. “Anubis” is the Ancient Egyptian god of death and mummification. We chose this name because the anatomical analysis of the fossils uncovered a strong relationship between the whale’s jaw and skull, which suggests that the whale’s bite was extremely strong — stronger than a crocodile’s fatal bite.

MM: Are there any more fossils that need to be examined in the same way?

HS: Too many. The easy way is to ask foreigners to conduct these studies. We could have chosen this route years ago with this whale, but we decided to wait until we found an Egyptian researcher who was passionate about studying the fossils themselves, which is what happened with our masters student Abdallah Gohar, who led this research discovery.

MM: Were the discovered fossils kept under the protection of the Environment Ministry?

HS: The fossils should typically be left in the location where they are discovered. There are fossil sites that I left in 2008 in the hope of finding researchers who are excited about studying them.

But one of the main challenges we face is the possibility of tampering with the fossils. At the end of the day, these are animal bones in which organic matter has been replaced by minerals. So they usually look like rocks, stones or bricks in the desert that non-specialists cannot identify as animals that lived millions of years before humans walked the Earth. So sometimes people kick them around, stand on them and break them.

A few years ago, I, along with a research team from the Mansoura University Paleontology Center, discovered a dinosaur. We started restoring it in the fossil site and prepping it to be transferred to the center’s museum. But before we could finish, someone went to the site and destroyed the fossils, then it was over. However, shortly afterward, we discovered fossils of another dinosaur in Mansoura. We called it “Mansoura-saurus” and it’s now displayed inside the museum in Mansoura University. The place is accessible to students but also to scientists from around the world who have discovered dinosaur fossils and want to compare them to the Egyptian dinosaur.

MM: Generally speaking, how do we protect fossils?

HS: We need to do more discovery expeditions and train students who are passionate about working in this field, because we cannot exercise control over what happens in the desert, we cannot protect every rock in the desert. I’m sure that due to the construction of new cities, many fossils have been inadvertently destroyed. When someone sees a strange object as they are digging, they should tell us right away. But unfortunately, many people prefer not to do that as it might delay the construction process.

Sometimes, we ask the Environment Ministry to designate a place as a natural reserve, which happened in many areas in Fayoum, but even despite this, there are many violations. For example, one of the most important fossil sites I have ever seen was an area in Fayoum that was turned into a tomato farm. An empty plot of land was taken by squatters and suddenly turned into a tomato farm and that was it. The fossils were gone forever. The same thing happens in the Beheira Oasis. People build on top of dinosaur fossils.

MM: How does this discovery help Fayoum?

HS: The discovery will promote scientific and academic tourism to Fayoum. Scientists and researchers will come here to study the species of whales that we have and the evolutionary processes of moving from terrestrial life to marine life.