The recent news that microplastics have been detected in human breast milk is the latest indication that these tiny fragments are everywhere.

Researchers found that microplastics — usually defined as pieces of plastic less than 5mm in size — were present in three-quarters of breast milk samples taken from 34 women who had given birth in Rome, Italy.

Similarly, just a few months earlier, in July, researchers in the Netherlands detected microplastics in a range of meat and milk products. Scientists have also found microplastics in beverages and seafood.

This widespread contamination of food and drink should not come as a surprise, because microplastics are being found almost everywhere. In June it was revealed researchers had even discovered them in fresh Antarctic snow.

The microplastic food chain

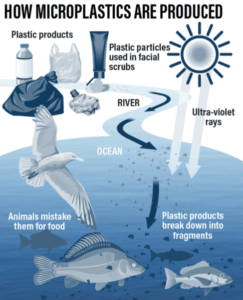

Many microplastics end up, or are formed, in the sea, allowing them to spread around the globe and absorb toxins. Some of these toxins may have been released into the environment decades ago.

Marine microplastics may enter the food chain by being eaten by progressively larger organisms until, eventually, they can be consumed by people eating seafood. Fish, scallops, mussels and oysters have been all found, in some instances, to be contaminated.

“They can be formed by accident or they’re deliberately produced,” says Dan Eatherley, a British environmental consultant and author who has worked on ways to reduce plastic waste with organisations including Google, Greenpeace and the UK government.

So-called primary microplastics are those that are deliberately produced, such as the microbeads in some cosmetics, while secondary microplastics are formed when waste plastics break down in the environment, often, Mr Eatherley says, due to the action of waves and rocks in the sea.

“There’s a lot of plastic that gets into the ocean from nets and other plastic gear fishers use, and then there’s plastic packaging that doesn’t get properly recycled and is instead washed into rivers and out to sea,” he says.

Mr Eatherley suggests that individuals can try to reduce their use of single-use plastics, such as by using refillable drinks containers and avoiding plastic cutlery.

The UK’s Natural History Museum says plastic cutlery is used for an average of just three minutes, but can remain in the environment for hundreds of years.

Because plastic is “built into the entire economy of modern society”, Mr Eatherley says, avoiding its use altogether is not easy.

“We instead need to shift to a more circular economy, where all of the plastic we use gets captured and recycled,” he says.

“At the moment, though, this is difficult because so many different types of plastic are used, making it hard to separate them.”

Laboratory studies indicate that microplastics can be harmful to human cells, but studies conclusively showing negative impacts on human health are lacking.

Many UAE residents may wonder whether the bottled water they consume has an impact on their health.

A 2018 study by researchers in Brazil, Portugal and the US, who looked at bottled water from nine countries, found that 93 per cent of samples contained microplastics, mostly plastic fragments, with fibres the next most prevalent category.

Two years later the publisher Consumer Reports tested 47 bottled waters and found Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs), known as “forever chemicals” because they linger in the environment, in “many products”.

These chemicals, the source of which was unclear, have been associated with developmental changes, cancer and harm to the immune system, among other effects.

In the majority of still water samples, PFAS levels were below one part per trillion, while a slight majority of carbonated waters were above this threshold. In nearly all samples, heavy metal quantities were within safety limits.

Clothing

Washing clothes adds huge numbers of microplastic particles to the environment. Figures published by the Natural History Museum say a single load of washing can release as many as 700,000 individual fibres. Narrower than a human hair, these tend not to be removed by filtration systems, so find their way into waterways and, ultimately, the sea. The Marine Conservation Society says domestic and industrial washing cycles may generate 35 per cent of primary microplastics. Laundry bags are available to help reduce microplastic pollution from washing machines.

Car tyres

These are one of the biggest sources of microplastic pollution because, as any driver knows, they wear out. As little as one fifth of tyre content is natural rubber with much of the rest being human-made substances, including plastics. Friends of the Earth, the environmental organisation, says half a million tonnes of plastic fragments are released from tyres each year on Europe’s roads. A large proportion of these fragments end up in rivers and oceans after being washed into drains by rainwater.

Toiletries and cosmetics

Numerous products contain intentionally added microplastics or microbeads, which may be eaten by fish or birds that mistake them for food. Colgate, the toothpaste company, says microbeads are added for various purposes, including to improve shelf life, add bulk, allow the timed release of active ingredients and as abrasives or exfoliants. Some countries have restricted the use of microbeads, such as the US with its 2015 Microbead-Free Waters Act, which “prohibits the manufacturing, packaging and distribution of rinse-off cosmetics containing plastic microbeads”.

Packaging

Because plastic does not biodegrade, plastic items such as food packaging, drinks bottles and the like are physically broken down into smaller pieces, which ultimately become microplastics. More than eight billion tonnes of plastic has been produced over time, less than 10 per cent of which has been recycled. About 12 per cent is incinerated, the UK’s University of Nottingham says, leaving the rest in landfill sites or the environment.

Dust

A significant proportion of dust in the air consists of microplastics, some of which may contain toxic materials such as pesticides and heavy metals, and may be breathed in. Carpets and paint are sources of this microplastic dust, although categories above, such as tyres and, in particular, clothing, are also key culprits. Echoing the global movement of plastic in the oceans, this dust can travel long distances when it is lifted high into the atmosphere and transported by air currents.