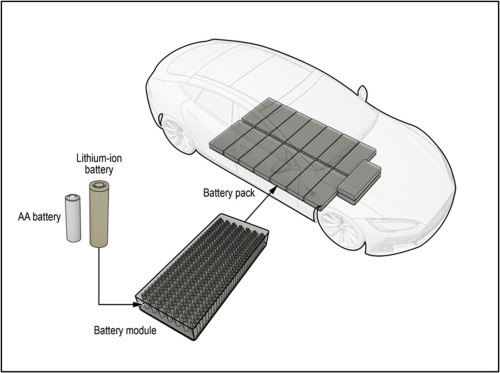

The battery of electric cars is more extensive and heavier; it consists of several hundred separate lithium-ion cells, each of which must be disassembled separately.

Recycling and disposal of electric car batteries could become a significant problem in 10-15 years, says Paul Anderson of the University of Birmingham, BBC reports.

By 2030, the EU plans to launch 30 million electric cars. “This is an unprecedented case of such a growth rate of a completely new product,” says Anderson.

While traditional lead-acid batteries used in conventional cars are being actively recycled, the same cannot be said of lithium-ion batteries.

“It is complicated to get data on the recycling of lithium-ion batteries in the world, currently called the figure of about 5%. But in some parts of the world, the figure is much lower,” says Anderson.

Source: National Transportation Safety Board

Now electric car manufacturers are trying to recycle batteries. For example, Nissan installs old Leaf batteries on mobile cars that deliver parts to the company’s plants. Volkswagen has opened the first battery recycling plant in Salzgitter, Germany, producing raw materials for producing new batteries: copper, aluminum, lithium, manganese, cobalt, and graphite. Similarly, the extraction of metals from used batteries is established by Renault, and not only its production.

The problem with recycling lithium-ion batteries is that in the process, most of the elements are lost to the so-called black mass – a mixture of lithium, manganese, cobalt, and nickel, which requires further energy-intensive processing.

Manual disassembly allows you to restore most of these materials more effectively but requires human labor. This means that in Europe, such work is too expensive, which makes the project economically unprofitable, and in countries with cheap labor, such as China, working conditions are often unacceptable.

So the question is whether it will be possible to invent effective automation of battery recycling.

At the same time, efficient recycling of batteries could solve the problem of raw materials. For example, Britain does not have natural reserves for battery production. “The old battery is a kind of mining in Europe,” says Jean-Philippe Ermine, Renault’s vice president of strategic environmental planning.

“The speed with which we are developing this industry is frightening,” said Paul Anderson of the University of Birmingham.

He means the European market of electric cars. By 2030, the EU plans to launch 30 million electric cars.

“This is an unprecedented case of such a growth rate of a completely new product,” says Anderson. He is also co-director of the Birmingham Center for Strategic Elements and Materials.

Electric cars can have a neutral level of carbon emissions throughout their life cycle. Still, scientists are worried about what will happen to their batteries, which contain toxic substances and, without proper disposal, can cause significant damage to the environment.

What will our life be like with electric cars?

“In 10-15 years, when there are a lot of old electric cars, it is essential to establish a processing industry,” he said.

The internal structure of electric cars is very similar to ordinary cars, but there is a fundamental difference – its batteries. While traditional lead-acid batteries are being actively recycled, the same cannot be said of lithium-ion versions in electric vehicles.

The battery of electric cars is bigger and heavier than in ordinary cars; it consists of several hundred separate lithium-ion elements, each of which must be disassembled separately. They contain dangerous components.

“It’s complicated to get data on the recycling of lithium-ion batteries in the world, now called the figure of about 5%,” says Anderson. “But in some parts of the world, this figure is much lower.”

However, there are clear guidelines in this regard in the European Union – suppliers of electric vehicles are responsible for ensuring that their products do not just go to landfills at the end of the life cycle, and manufacturers seek to give the batteries of their electric vehicles a second life.

For example, Nissan installs old Leaf batteries on mobile cars that deliver parts to workers at the company’s plants worldwide.

Volkswagen recently opened its first battery recycling plant in Salzgitter, Germany. In the pilot phase, the company plans to recycle up to 3,600 battery systems a year.

“Through recycling, we get the raw materials needed to make new batteries, such as copper, aluminum, lithium, manganese, cobalt, and graphite,” said Thomas Tidier, head of recycling planning at Volkswagen Group Components.

Renault is not far behind in resolving this issue.

The French automaker, together with Veolia, a leader in optimized resource management, and the Belgian research company Solvay have formed a partnership that provides a closed cycle of electric vehicles when recycled metals go to recycling new batteries.

We aim to cover 25% of the recycling market, and of course, this will fully cover Renault’s needs,” said Jean-Philippe Ermine, Renault’s vice president of strategic environmental planning.

“It’s a very open project – it’s not just Renault batteries. We recycle all batteries, as well as waste from battery plants.”

This question also attracts the attention of scientists from the Faraday Institute. They want to optimize and simplify the disposal of electric car batteries.

“We want to turn this into an efficient and cost-effective industry,” says Anderson, project manager.

Now, for example, most of the battery cells are lost in the process of processing to the so-called black mass – a mixture of lithium, manganese, cobalt, and nickel, which requires further energy-intensive processing.

Manual disassembly allows you to restore most of these materials more effectively, but it has its drawbacks.

According to Gavin Harper of the Faraday Institute, automating battery disposal will make it more economical and safer.

“In some world markets, such as China, labor and environmental requirements are less stringent, and working conditions are unacceptable in the Western context,” said Gavin Harper of the Faraday Institute. “But labor in Europe is very expensive; it makes the project economically unprofitable. “

The way out, he said, is automation.

“If you can automate processes, we can make them cost-effective.”

Indeed, there are strong economic arguments in favor of recycling electric car batteries. This is, not least, the fact that most of the components for the production of batteries are difficult to find in Europe.

“On the one hand, there is the problem of waste management, and on the other hand, it’s a great opportunity because, for example, Britain doesn’t have natural reserves for battery production,” says Harper.

Therefore, recycling old batteries is the best way to ensure a constant supply of new ones for the manufacturer.

“We need to get these materials because they are of strategic importance for mobility and industry in general,” said Jean-Philippe Ermine.

“We don’t have access to these resources other than recycling. An old battery is a kind of mining in Europe.”